Vlak na Jesenicah čaka na odhod proti Ratečam (hrani: GMJ).

A train at the Jesenice station about to depart towards Rateče (held by: Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

Pričujoča razstava Zgodovina ob tirih – Zgodbe z železnice Jesenice–Trbiž se s svojimi pripovedmi ne osredotoča močno na tehnične in tehnološke vidike nekdanje železnice, ki je povezovala Jesenice s Trbižem. Temelj razstave predstavljajo posamezne epizode oziroma posamezne zgodbe in drobci, povezani s tehniško, vojaško, kulturno in vsesplošno vsakodnevno zgodovino železnice v Zgornjesavski dolini. Ti drobci življenja ob železnici tako vsebujejo pripovedi – vse od gradnje železnice v drugi polovici 19. stoletja pa do dogodkov prve svetovne vojne, obdobja med obema vojnama pa do druge svetovne vojne, ko železnica postane tudi strateški cilj zavezniških letalskih napadov. Povojni čas je zaznamovan predvsem z vsakodnevnim življenjem, s turizmom in športom, med dogodki pa izstopa tudi tragična železniška nesreča pri Belci, vse do opustitve proge leta 1966.

Pozornemu obiskovalcu slikovite Gornjesavske doline danes ne uidejo ostanki mostov, trase železnice, nekdanje železniške postaje in čuvajnice ter drugi materialni ostanki, ki so ostali za »železno cesto«. Kljub temu da zgodbe, ki povezujejo nekdanje in sedanje življenje ob njej, počasi tonejo v pozabo, se jih še vedno da iztrgati preteklosti in jih deliti ter ohraniti za zanamce. Kot so zapisali ob ukinitvi železnice v časopisu Glas: »Utihnil je glas lokomotiv in ostal bo le spomin.«

Avtorja razstave: dr. Uroš Košir in Aleš Bedič – Društvo za raziskovanje in proučevanje vojaške in tehniške dediščine Vršič

Koordinatorja: Daša Čopi in dr. Marko Mugerli, Gornjesavski muzej Jesenice

Slikovno in fotografsko gradivo: dr. Uroš Košir, Brane Horvat, France Voga, Anamarija Zupančič, Gornjesavski muzej Jesenice, Zgodovinski arhiv Ljubljana (enota Kranj), Arhiv Republike Slovenije, Muzej novejše in sodobne zgodovine Slovenije, Župnija Kranjska Gora, Narodni muzej Slovenije, Science Museum London, SAAF WW2 Heritage Site, American Air Museum London.

Priprava in konservacija razstavljenih predmetov: Stane Staš Beton, Gornjesavski muzej Jesenice in dr. Uroš Košir

Lektura: Monika Križaj, s. p.

Prevod in lektura v angleškem jeziku: Adele Gray, s. p.

Oblikovanje: Studio Čuk, Jasna Čuk Kolavčič, s. p.

Tisk: Grafika Zupan, Gozd Martuljek

Produkcija: Gornjesavski muzej Jesenice, zanj Aljaž Pogačnik

HISTORY ALONG THE TRACKS – STORIES FROM THE JESENICE–TARVISIO RAILWAY

The stories of the History Along the Tracks – Stories from the Jesenice-Tarvisio Railway exhibition does not focus strongly on the technical and technological aspects of the former railway that connected Jesenice to Tarvisio. The exhibition is based on individual episodes or stories and fragments related to the technical, military, cultural and general everyday history of the railway in the Upper Sava Valley. These fragments of life along the railway encompass stories – everything from construction of the railway in the second half of the 19th century to the events of World War I, as well as the interwar period up to World War II, when the railway became a strategic target for Allied air attacks. The post-war period is mainly marked by everyday life, tourism and sports, with the tragic railway accident in Belca standing out among the events, until the railway line was abandoned in 1966.

Today, attentive visitors to the picturesque Upper Sava Valley cannot fail to notice the remains of bridges, railway tracks, former railway stations and guardhouses, as well as other material remains left behind by the so-called ‘iron road’. Despite the fact that the stories that connect past and present life alongside it are slowly fading into oblivion, they can still be wrenched from the past and shared and preserved for posterity. Upon closure of the railway, the newspaper Glas wrote: ‘The sound of the locomotives has fallen silent and only a memory will remain.’

Exhibition authors: Dr. Uroš Košir and Aleš Bedič – Association for the Research and Study of the Military and Technical Heritage Vršič

Exhibition coordinators: Daša Čopi and Dr. Marko Mugerli, Upper Sava Museum Jesenice

Pictorial and photographic material: Dr. Uroš Košir, Brane Horvat, France Voga, Anamarija Zupančič, Upper Sava Museum Jesenice, Historical Archive Ljubljana (Kranj unit), Archive of the Republic of Slovenia, National Museum of Contemporary History of Slovenia, The Parish of Kranjska Gora, National Museum of Slovenia, Science Museum London, SAAF WW2 Heritage Site, American Air Museum London.

Preparation and conservation of exhibition objects: Stane Staš Beton, Upper Sava Museum Jesenice and Dr. Uroš Košir

Proofreading: Monika Križaj, s. p.

Translation and proofreading in English: Adele Gray, s. p.

Design: Studio Čuk, Jasna Čuk Kolavčič, s. p.

Print: Grafika Zupan, Gozd Martuljek

Production: Upper Sava Museum Jesenice, represented by Aljaž Pogačnik

- RAZVOJ ŽELEZNICE NA PODROČJU DANAŠNJE SLOVENIJE

Konec 18. stoletja so predvsem v Veliki Britaniji pričeli uporabljati parne stroje kot pogonsko sredstvo sprva še zelo slabotnih in okornih lokomotiv. Prva železniška proga Stockton–Darlington je bila odprta leta 1825, vendar so bile takratne lokomotive preslabotne in nezanesljive, zato za dokončno uveljavitev parnih lokomotiv štejemo leto 1829. V tem letu je inženir George Stephenson izdelal znamenito parno lokomotivo, imenovano »Raketa«, ki je ob zmernem bremenu dosegla največjo hitrost približno 48 km/h. Po letu 1830 se je pričel skokovit razvoj vedno močnejših in tehnično čedalje bolj razvitih lokomotiv ter gradnja železniškega omrežja po vsem svetu. Takratne države so zelo hitro spoznale izreden pomen železnice za nadaljnji razvoj. Nič drugače ni bilo v stari Avstriji, ki je pričela z izgradnjo železniškega omrežja v letu 1827. V letu 1837 je bila tako odprta proga Dunaj–Krakow, nedolgo zatem pa se je začelo tudi načrtovanje tako imenovane Južne železnice, ki bi povezala Dunaj s pomembno luko Trst.

Prva železniška proga, zgrajena v današnji Sloveniji, je bil odsek tako imenovane Južne železnice, ki je bil speljan od Gradca (Graz) preko Maribora do Celja. Pod vodstvom inženirja Carla von Ghega je prvi vlak na ozemlje Slovenije zapeljal 1. novembra 1845, in sicer na poskusni vožnji iz Gradca do Pesnice pri Mariboru, 2. junija 1846 pa je sledila slavnostna otvoritev železniške proge Gradec–Celje. Sledila je gradnja železniške proge na odseku Celje–Ljubljana, ki so jo pričeli načrtovati v letih 1842 in 1843. Gradnja tega odseka se je izkazala za zelo zahtevno, razmišljali so celo o treh možnih trasah. Na koncu so se odločili za traso od Celja preko Zidanega Mostu, Hrastnika, Trbovelj, Zagorja, Litije do Ljubljane. Gradnja se je začela leta 1845. Samo za gradnjo železniškega mostu čez reko Savinjo v Zidanem Mostu so potrebovali tri leta, in sicer od 1846 do 1849. Kako zahtevna je bila gradnja, priča tudi dejstvo, da so za potrebe gradnje poleg velikega števila domačih zaposlili skoraj 12.000 tujih delavcev. Prvi vlak je po novi progi pripeljal 18. avgusta 1849, uradna otvoritev je bila 16. septembra 1849.

Sledila je še zadnja faza gradnje Južne železnice na odseku med Ljubljano in Trstom. Tudi gradnja tega odseka proge je bila tehnično izredno zahtevna, predvsem zaradi mehkega terena Ljubljanskega barja in kamnitega kraškega dela. Za utrjevanje trase na Ljubljanskem barju z nasipanjem materiala so potrebovali tri leta. V tistem času so zgradili tudi največji zidani most v srednji Evropi, 561 metrov dolg in 38 metrov visok borovniški viadukt. Prvi vlak je po novi progi zapeljal 20. novembra 1856, 27. julija 1857 so progo tudi uradno odprli.

- THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE RAILWAY IN THE TERRITORY OF TODAY’S SLOVENIA

At the end of the 18th century, especially in Great Britain, steam engines began to be used as a means of propulsion for initially very ineffectual and cumbersome locomotives. The first railway line – Stockton-Darlington – opened in 1825, however the locomotives of that time were too ineffectual and unreliable, hence 1829 counts as being the year when steam locomotives were finally introduced. In that year, the engineer George Stephenson built the famous ‘Rocket’ steam locomotive, which reached a maximum speed of about 48 km/h with a moderate load.

After 1830, the rapid development of increasingly powerful and technically more developed locomotives began, as did the construction of railway networks all over the world. At that time, countries very quickly realised the extraordinary importance of the railway for further development. It was no different in the Austrian Empire, which in 1827 started to construct a railway network. The Vienna-Krakow line opened in 1837, and not long after that planning began of the so-called Southern Railway, which would connect Vienna with the important port of Trieste.

The first railway line built in today’s Slovenia was a section of the so-called Southern Railway, which ran from Graz via Maribor to Celje. Under the leadership of engineer Carl von Gheg, the first train entered the territory of Slovenia on 1st November 1845, on a test run from Graz to Pesnica near Maribor, followed by the ceremonial opening of the Graz-Celje railway line on 2nd June 1846. This was followed by construction of the railway line on the Celje-Ljubljana section, planning of which began in 1842 and 1843. The construction of this section turned out to be very demanding and the engineers even considered three possible routes. In the end, they opted for the route from Celje via Zidani Most, Hrastnik, Trbovlje, Zagorje and Litija to Ljubljana. Construction began in 1845. Construction of a railway bridge over the Savinja River in Zidani Most took three years from 1846 to 1849. The fact that in addition to a large number of local workers almost 12,000 foreign workers were also employed is testimony to the demanding nature of the construction. The first train arrived on the new line on 18th August 1849, and the line was officially opened on 16th September 1849.

The final phase of construction of the Southern Railway on the section between Ljubljana and Trieste followed. The construction of this section of the track was also technically extremely demanding, mainly due to the soft terrain of the Ljubljana Marshes and the rocky karst part. It took three years to fortify the route on the Ljubljana Marshes by filling it with material. At that time, the largest brick bridge in Central Europe was also built, the 561-metre-long and 38-metre-high Borovnica viaduct. The first train ran on the new line on 20th November 1856 and the line was officially opened on 27th July 1857.

- GRADNJA ŽELEZNICE JESENICE–TRBIŽ

Gradnja proge Ljubljana–Trbiž v času gradnje Južne železnice ni bila načrtovana. Predvsem po zaslugi dr. Lovra Tomana, poslanca v takratnem deželnem zboru, in pa dejstva, da je bila Gorenjska v tem obdobju najbolj industrializiran del v današnji Sloveniji (takrat del Avstro-Ogrske 1867–1918), so poslanci deželnega zbora podprli predlog izgradnje gorenjske železnice. Po sprejetju ustreznih zakonskih določil za gradnjo 102 kilometra dolge železnice med Ljubljano in Trbižem je bil objavljen razpis za izvedbo del. Ponudbo so oddala tri podjetja – Ljubljanski konzorcij, Stavbno podjetje G. Pongratz in pa k.k. privilegierte Kronprinz Rudolf Bahn (KRB). Slednje podjetje je na natečaju zmagalo, z gradnjo so pričeli spomladi 1869 na več odsekih hkrati. Dela je opravljalo približno 12.000 delavcev, v večini so bili to tuji delavci, progo pa so gradili v izmenah, tudi ponoči. Proga je bila v celoti zgrajena v rekordnem času dveh let, prva preizkusna vožnja vlaka od Ljubljane do Trbiža je bila opravljena 15. oktobra 1870, uradni preizkus je sledil še 26. in 27. oktobra 1870, za datum uradne otvoritve proge pa je bil določen 14. december 1870. Na ta dan je po progi zapeljal prvi potniški vlak. Leta 1873 je bila zgrajena še železniška povezava med Trbižem in Beljakom, proga je tako postala del omrežja tako imenovane Rudolfove železnice. Podjetje KRB je kmalu po izgradnji gorenjske železnice zašlo v finančne težave, katerih posledica je bil stečaj podjetja in prevzem železnice s strani države leta 1880. Rudolfove železnice se takrat tudi preimenujejo v Staatsbahnen – Državne železnice.

Zagotovo najlepši in najbolj razgiban del železnice poteka od Mojstrane do Kranjske Gore. Na tem odseku je bilo v dolžini dobrih 15 km zgrajenih šest železniških mostov (Belca preko hudournika Belca, Podkluže (Podkuže) preko Save, Tabre preko Save, Gozd Martuljek preko hudournika Hladnik, Gozd Martuljek prek Save, Kranjska Gora preko Pišnice), šest podhodov pod progo, ki so bili namenjeni nemotenemu prehodu kmečkih vozov, živine ipd. Vsi podhodi so širine 2,5 m, višine pa so različne in so odvisne od višine železniškega nasipa. V primeru poplav so ti podhodi služili tudi pretakanju poplavnih voda.

- CONSTRUCTION OF THE JESENICE–TRBIŽ RAILWAY

Construction of the Ljubljana-Tarvisio line was not planned during construction of the Southern Railway. Mainly thanks to Dr. Lovro Toman, a member of the regional assembly at the time, and the fact that Carniola was the most industrialised part of today’s Slovenia (then part of Austria-Hungary 1867–1918), the members of the regional assembly supported the proposal to build the Carniola railway. Following adoption of the relevant legal provisions for construction of the 102-kilometre-long railway between Ljubljana and Tarvisio, a tender for the execution of the works was published. Three companies submitted offers – the Ljubljana Consortium, Construction Company G. Pongratz, and k.k. privilegierte Kronprinz Rudolf Bahn (KRB). The latter company won the tender and construction of several sections consecutively began in the spring of 1869.

The work was carried out by around 12,000 workers, the majority of whom were foreign, who carried out the work in shifts, including night shifts. The track was constructed in its entirety in record time – two years – and the first train test run from Ljubljana to Tarvisio took place on 15th October 1870. This was followed by an official test on 26th and 27th October 1870, and 14th December 1870 was set as the date for the official opening of the track. The first passenger train ran on the track on that day. A railway connection between Tarvisio and Villach was constructed in 1873, thus the track became part of the network of the so-called Rudolph Railway. Soon after construction of the Carniola railway, the company KRB found itself in financial difficulties, as a result of which it went bankrupt and the railway was taken over by the state in 1880. At that time, the Rudolph Railway was renamed as Staatsbahnen – State Railway.

Undoubtedly, the most beautiful and varied part of the railway runs from Mojstrana to Kranjska Gora. Six railway bridges were constructed on this section over a length of around 15 kilometres (at Belca across the Belca mountain stream, at Podkluže (Podkuže) across the Sava River, at Tabre across the Sava River, in Gozd Martuljek across the Hladnik mountain stream, in Gozd Martuljek across the Sava River and in Kranjska Gora across the river Pišnica). In addition, six underpasses beneath the track were built to enable the uninterrupted passage of farm carts, cattle, etc. All the underpasses were 2.5 metres-wide and the height varied depending on the height of the railway embankment. During flooding, these underpasses served as a run-off area for flood water.

Kilometrski kamen podjetja k. k. Kronprinz Rudolf Bahn (foto: U. Košir, 2023).

A kilometre stone of the company k. k. Kronprinz Rudolf Bahn (photo: U. Košir, 2023).

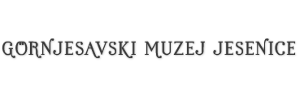

3. OBISK FRANCA JOŽEFA

Julija 1883 so bili za Štajersko in Kranjsko prav posebni dnevi, saj je ob šesto letnici habsburške vladavine obe deželi obiskal sam cesar Franc Jožef I. Na Gorenjskem je bil 16. in 17. julija. Časopis Slovenec je kmalu po svečanem obisku zapisal: »To so bili dnevi, da takih nismo doživeli še ne mi in ne naši očetje! Mnogo cesarjev, med temu tudi avstrijskih, videla je že Ljubljana, pa tako sijajno ni bil sprejet nobeden; reči celo smemo, da ga ni kralja ne cesarja in sploh vladarja, kteri bi mogel reči, da je svojim podložnim toliko priljubljen kakor ravno naš Franc Jožef.« Po potovanju skozi Mengeš, Kamnik, Cerklje in Šenčur se je cesar z vlakom odpravil iz Kranja v Lesce, si ogledal Begunje in Bled, nato pa z Lesc po železnici nadaljeval svojo pot proti Trbižu.

Visoki obisk so pozdravili med drugimi tudi na Dovjem: »Sv. Aleša dan 17. t. m. ob pol 6 zjutraj je dolška fara z banderi in šolska mladost s svojo zastavo na tukajšnji postaji pozdravila svojega cesarja, ko je odhajal proti Išelnu. Vrhovi bližnjih gora so bili pokriti s snegom« (časopis Slovenec).

Prihod cesarja je bil pomemben tudi za Rateče, zato so se množično udeležili zborovanja na bližnji železniški postaji. Rateški župnik Josip Lavtižar je prihod Franca Jožefa I. v Rateče opisal tako: »1883. Pomenljivo leto za Rateče radi tega, ker se je peljal presvetli cesar skozi gorenjsko dolino. Dne 17. julija 1883 je bila zgodaj zjutraj vsa vas po koncu. Ob pol šestih zjutraj se je zbrala šolska mladina v šolski sobi ter se od tu podala na kolodvor. Kmalu po šesti uri je dospel dvorni vlak, s katerim se je pripeljal cesar Franc Jožef. Ratečanov je bilo nad 600 zbranih na kolodvoru. Sprejeli so Njegovo Veličanstvo z navdušenim »živio« – klici. Vlak se je počasi vozil skozi postajo, cesar je slonel pri oknu in odzdravljal. Peljal se je iz Ljubljane na Trbiž.«

3. A VISIT BY EMPEROR FRANZ JOSEPH

July 1883 was a very special day for Styria and Carniola, because on the 600th anniversary of the Habsburg rule, Emperor Franz Joseph I himself visited both regions. He visited Upper Carniola on 16th and 17th July. Shortly after the ceremonial visit, the following appeared in the newspaper Slovenec: ‘These were days that neither we nor our fathers had ever experienced before! Ljubljana has seen many emperors, including Austrian ones, but none were received so enthusiastically; we can even say that there is no king, no emperor, and no ruler at all, who could say that he is as popular with his subjects as our Emperor Franz Joseph.’ After travelling through Mengeš, Kamnik, Cerklje and Šenčur, the emperor left Kranj by train to Lesce, visited Begunje and Bled, and then continued his journey from Lesce to Tarvisio by railway.

The dignified visit was also welcomed in Dovje, among others: ‘At half past six in the morning on St. Alexius Day – 17th July – the Dovje parish greeted their emperor at the station here as he was leaving for Bad Ischl in Austria. The tops of the nearby mountains were covered with snow’ (Slovenec newspaper).

The arrival of the emperor was also important for the people of Rateče, so they took part in a gathering at the nearby railway station. The Rateče parish priest, Josip Lavtižar, described the arrival of Franz Joseph I in Rateče as follows: ‘1883. A significant year for the people of Rateče because the most illustrious emperor passed through the Upper Sava Valley. Early in the morning of 17th July 1883, the whole village was up and around. At half past six in the morning, school youths gathered in the school room and from there went to the railway station. Shortly after six o’clock, the court train carrying Emperor Franz Joseph arrived. Over 600 people from Rateče gathered at the station. They received His Majesty with enthusiastic shouts of ‘živio’ (Hello). The train was moving slowly through the station, the emperor was resting by the window and returning their greetings. He was going from Ljubljana to Tarvisio.’

Franc Jožef I. ob svojem 60. jubileju vladanja (hrani: U. Košir).

Franz Joseph I on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of his reign (held by: U. Košir).

4. ŽELEZNICA MED PRVO SVETOVNO VOJNO

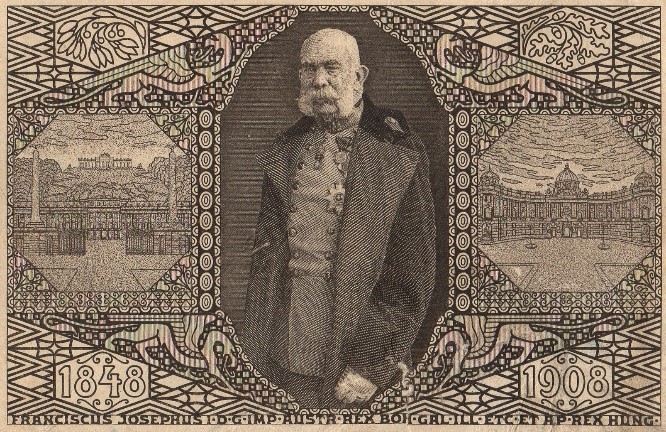

V času prve svetovne vojne je imela železnica v Gornjesavski dolini velik pomen. Po njej so na fronto že takoj po začetku vojne leta 1914 odhajali domačini in po njej so prihajali vojaki in neizmerne količine vojaškega materiala, namenjenega bojem na soški fronti v letih 1915–1917. Zaradi pomena železničarskega prometa za vojaške namene so imeli vojaški transporti prednost pred civilnimi vlaki, potovanja med kraji pa so postala dolgotrajna. Kranjskogorski župnik Andrej Krajec je zapisal, da je že leta 1914, ko na našem ozemlju še ni bilo vojne, pot do Ljubljane trajala kar šest ur namesto dveh. Po začetku bojev avstro-ogrske z italijansko vojsko na soški fronti so se železniški transporti izjemno povečali, kar so občutili tudi prebivalci Gornjesavske doline. Andrej Krajec je zapisal: »Od dneva napovedi vojne dan za dnevom so vozili vlaki, menda nad sto v 24 urah. Nikoli ni bilo miru – po dnevi vpitje in drvenje na cesti, po noči tulenje in zvižganje vlakov, vpitje vojaštva, preklinjevanje poveljnikov, za me grozno, ker imam stanovanje na kolodvorski strani – vojake namenjene na soško fronto, ker so bili vsi prelazi v Rablju in Trbižu v območju italijanskih granat. Vsi vojaški transporti, vsi topovi, vsa municija, vsa živila, sploh vse vojaštvo, vse potrebščine za vojno, vse, prav vse so spravili skozi Kranjsko Goro in to večinoma po noči. Hiša se mi je vedno tresla in okna so šklepetala, da včasih, kadar je bilo to izjemoma po dnevi, nismo mogli govoriti v sobi, se nismo mogli razumeti, je bilo še dosti hujši, kakor se mora tu vsled pomanjkanja prostora in časa sploh opisati. Z malimi izjemami je to trajalo skoro dve leti. Kako sem to pri svojih živcih mogel to prenašati, ne vem; rečem samo to, rajši umreti, kakor da bi moral vse to še enkrat prestati.«

Zaradi povečanega železniškega prometa in količine tovora je bila kranjskogorska železniška postaja razširjena, vključevala pa je razkladalne rampe in kar devet tirov. Posamezni tiri so bili speljani do vojaških skladišč (nem. Fassungsstelle), od koder so tovor postopoma spravili na tovorno žičnico, ki je imela začetno postajo v Kranjski Gori, tik ob glavnem skladišču materiala. V avstro-ogrski vojski so s tovornimi žičnicami upravljali pripadniki železničarskega polka (nem. Eisenbahnregiment), kranjskogorska oziroma »vršiška« žičnica pa je nosila oznako Seilbahn 17.

4. THE RAILWAY DURING WORLD WAR I

During World War I, the railway was of great importance in the Upper Sava Valley. Immediately after the start of the war in 1914, local people left to the frontline on it and soldiers arrived along with immense quantities of military material intended for the battles on the Soča Front in 1915-1917. Due to the importance of railway transport for military purposes, military transports took precedence over civilian trains, thus journeys between places became lengthy. The Kranjska Gora priest Andrej Krajec wrote that in 1914, when war had not yet broken out on the territory of Slovenia, that the journey to Ljubljana took six hours instead of two. After the beginning of the fighting between Austria-Hungary and the Italian army on the Soča Front, railway transport increased tremendously, which had a knock-on effect on inhabitants of the Upper Sava Valley. Andrej Krajec wrote:

‘From the day war was declared, trains were running day after day, seemingly over a hundred in 24 hours. There was never peace – during the day shouting and rushing on the road, at night the howling and whistling of trains, the shouting of the military and swearing of the commanders. It was terrible for me because my apartment is on the station side – soldiers destined for the Soča Front because all the crossings in Cave del Predil and Tarvisio were in the area of Italian shells. All the military transports, all the cannons, all the ammunition, all the foodstuffs, and particularly all the military and all the necessities for the war; everything, absolutely everything, was transported through Kranjska Gora, mostly at night. My building was always shaking and the windows rattling, sometimes, when it was exceptionally late in the day, we couldn’t hear ourselves speak or understand each other, it was much worse than can be described here due to the lack of space and time. With few exceptions, this went on for almost two years. How, with my nerves, I could bear it, I don’t know; I can only say this, I would rather die than have to go through it all again.’

Due to increased rail traffic and the amount of cargo, the Kranjska Gora railway station was extended to include unloading ramps and as many as nine tracks. The individual tracks led to military warehouses (German: Fassungsstelle), from where the cargo was gradually transferred to the freight cableway, whose base station was in Kranjska Gora, right next to the main material warehouse. In the Austro-Hungarian army, freight cableways were operated by members of the railway regiment (German: Eisenbahnregiment), while the Kranjska Gora or the so-called ‘Vršič cableway’ bore the designation Seilbahn 17.

Vojaški transport na poti proti Kranjski Gori (hrani: U. Košir).

Military transport on the way towards Kranjska Gora (held by: U. Košir).

5. VAROVANJE ŽELEZNICE

Z obdobjem prve svetovne vojne in z življenjem ob železnici je povezana tudi tragična zgodba iz Kranjske Gore. Že takoj po italijanski vojni napovedi Avstro-ogrski monarhiji je v Kranjsko Goro prispela stotnija tako imenovanih mladostrelcev (nem. Jungschützen) iz Beljaka. Njihova naloga je bila varovanje cest, mostov in železnice pred morebitnimi sabotažami, zasedli pa so tudi prelaz Korensko sedlo.

Tragičen dogodek je se zgodil 26. junija 1915, ko se je Andrej Tarman z Loga pri Kranjski Gori, kjer je imel ob železnici svojo hišo s posestvom, vračal domov po nakupih iz Kranjske Gore. Kot je v Župnijski kroniki zapisal takratni župni Andrej Krajec, je bil Tarman »/…/ gluh na eno uho, na drugo je pa bolj malo slišal«. Na prehodu čez tire ga je s klicem in z naperjeno puško želel ustaviti mlad avstrijski »mladostrelec«. Župnik Krajec je nadaljevanje dogodka opisal takole: »Tarman ne sliši ter gre mirno naprej, poba pa ustreli. Strel sicer ne zadene prvič, a Tarman ga le sliši in začne bežati proti svoji hiši: zdaj pa se začne divji lov na ubogega človeka. Tarman naprej, poba s puško za njim strelja zaporedoma v teku, slednjič prideta do Tarmanovega hleva. Kaka dva metra od železniškega tira tu zadene strel ubogega reveža v desno nogo ter mu odbije kost – tibijo za dva decimetra dolžini. Tarman se zgrudi in skoro pol ure leži v svoji krvi, slednjič ga vendar spravijo pod streho in obvežejo, poklicali so me takoj, da ga previdim s svetimi zakramenti. Bilo ga je grozno videti, kako je trpel. Peljal sem se s Smeršnikovem vozom in kolesa so bila vsa krvava, ker smo šli skozi lužo krvi. Tarmana smo spravili v bolnico v Lj, telesno je okreval, a zbolel je dušno in hiral po raznih bolnicah – bil je večinoma na Studenem pri Lj. do letos. 13/4 t. l. ga pripeljejo skoro umirajočega na dom, kjer umre 15/4, zapusti 3 nedorasle otroke in vdovo.«

Za varovanje proge so bili sicer zadolženi tudi pripadniki varovalnih oddelkov, eden izmed takih pa je bil npr. črnovojniški oddelek za varovanje proge Mojstrana (nem. K. k. Landsturm-Eisenbahnsicherungsabteilung Mojstrana).

- PROTECTING THE RAILWAY

There is a tragic story from Kranjska Gora connected with the period of World War I and life along the railway. Immediately after Italy’s declaration of war against the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, a company of so-called young shooters (German: Jungschützen) from Villach arrived in Kranjska Gora. Their task was to protect roads, bridges and railways from possible sabotage, and they also occupied the Wurzen Pass (Slovene: Korensko sedlo).

The tragic event took place on 26th June 1915, when Andrej Tarman from Log near Kranjska Gora, whose house and estate was next to the railway, was returning home after shopping in Kranjska Gora. As Andrej Krajec, the parish priest at the time, wrote in the Parish Chronicle, Tarman was ‘…/ deaf in one ear and could barely hear in the other.’ At the crossing over the tracks, a young Austrian ‘Jungschütz’ tried to stop him by calling out and cocking his rifle. Krajec described the continuation of the event as follows:

‘Tarman doesn’t hear and walks calmly forward, but the lad shoots. The first shot doesn’t hit him, but Tarman hears it and starts running towards his house: that’s when the wild hunt for the poor man begins. Tarman goes forward, the lad with a rifle behind him fires in succession in a run, until they finally reach Tarman’s barn. Approximately two metres from the railway track the poor man is hit in the right leg with a shot that takes out his bone – twenty centimetres in length. Tarman collapses and lies in a pool of his own blood for almost half an hour, until he is finally moved to beneath the roof and bandaged up. I was immediately called to read him the Last Rites. It was terrible to see him suffer. I was on Smeršnik’s wagon and the wheels were covered in blood because we drove through a pool of it. We took Tarman to the hospital in Ljubljana, he recovered physically, but he became mentally ill and languished in various hospitals – he was mostly in Studeno near Ljubljana until 1916. On 13th April they brought him home, at death’s door, where he died on 15th April, leaving behind three young children and a widow.’

Members of the security departments were also in charge of guarding the track, one of which was e.g. the Landsturm railway security unit for the protection of the Mojstrana line (German: K. k. Landsturm-Eisenbahnsicherungsabteilung Mojstrana).

Avstro-ogrska vojaška straža pred tunelom pri Hrušici (hrani: GMJ).

Austro-Hungarian military guards in front of the tunnel at Hrušica (held by: Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

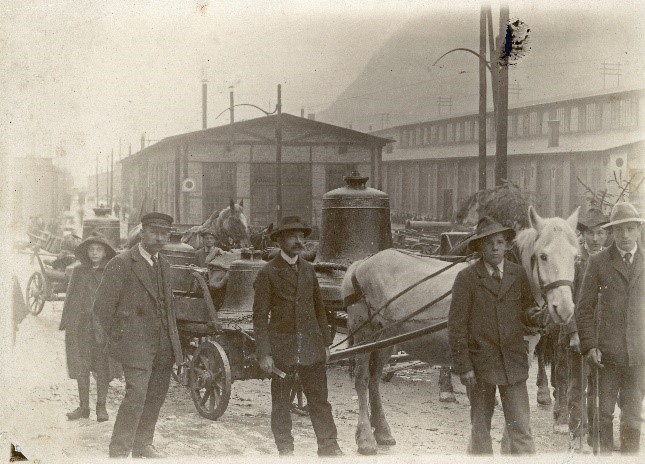

6. ODVZEM CERKVENIH ZVONOV

Zaradi pomanjkanja barvnih kovin, ki jih je vojna industrija potrebovala za izdelavo streliva in topov, je bil že leta 1915 objavljeni odlog o odvzemu zvonov, kar se je na območju Gorenjske ponekod zgodilo že v naslednjem letu. Po vaseh so ljudje lahko opazovali žalosten sprevod na vlakih naloženih zvonov, ki niso nikdar več klicali k svetim mašam, porokam in drugim praznikom ter nikdar več niso zvonili umrlim vaščanom v slovo. Rateški župnik Josip Lavtižar je ob tej priliki zapisal: »Dan 1. majnika 1917 je bil žalosten za vso župnijo. Prišli so vojaki in nam vzeli mali in srednji zvon za vojne namene. Vsakemu se je storilo milo pri srcu, ko sta ležala na tleh dolgoletna vabilca v cerkev in spremljevalca mrtvih župljanov na pokopališče. Župan – starosta g. Jožef Pintbah ju je peljal, okrašena s prvim pomladnjim cvetjem, s parom svojih močnih kobil na kolodvor. In ko je zvonovoma zvonil iz stolpa njun veliki tovariš zadnjo pesem v slovo, bile je vse ginjeno do solz, saj je visel mali zvon že od l. 1792 v linah rateškega zvonika, srednji pa od l. 1747. Upali smo, da nam ostane sedaj vsaj veliki zvon. Pa tudi temu se ni prizaneslo. Sneli so ga 27. avgusta 1917 in odpeljali bogvekam. Temu pa je zvonil v slovo naš najmanjši zvon, ki smo ga vzeli iz zvonika sv. Tomaža in ga obesili v zvonik župnijske cerkve. Samo ta nam je ostal.«

Odvzem zvonov in njihovo slovo je opisal tudi kranjskogorski župnik Andrej Krajec: »Da bi rešil veliki zvon, sem dal vse druge iz farne cerkve in Podkorenom, vse, razen najmanjšega. Radi starosti v župni cerkvi nisem mogel nobenega rešiti, ker so bili vsi 1868 leta preliti. Podkorenom je bil veliki in srednji prav častite starosti, pa sem za velikega vse žrtvoval. Slike govore zase dosti jasno, še uro, ob kteri se je to vršilo, vidimo. Zvonovi se tudi lahko ločijo po velikosti. Spremila sva jih z gosp. Kresom na kolodvor. Počakali smo podkorenjske, potem smo šli z verniki rožni venec moleč v sprevodu na kolodvor. Ljudstvo je bilo toliko ogorčeno, da sem se bal resnih nemirov. Akoravno sem bil sam do skrajnosti razburjen, sem moral z gospodom Kaplanom le ljudstvo miriti. Pred odhodom na kolodvor so jim cerkveni pevci zapeli še nekaj pesmic v slovo.«

- DISPOSSESSION OF CHURCH BELLS

Due to the lack of non-ferrous metals that the war industry needed for the manufacture of ammunition and cannons, a decree was published in 1915 on the dispossession of church bells, which took place in some places in the Upper Carniola area as early as the following year. People in villages watched sadly as the procession on trains went by loaded with bells, which were never again to ring for holy masses, weddings and other holidays, and also never again rang as a farewell to deceased villagers. On the occasion, the Rateče priest Josip Lavtižar wrote:

‘1st May 1917 was a sad day for the entire parish. Soldiers came and took the small and medium bells from us for war purposes. Everyone had a heavy heart when the long-time bells that beckoned people to the church and the companions of the deceased parishioners to the cemetery were lying on the ground. The mayor – the doyen Mr. Jožef Pintbah – transported the bells, decorated with the first spring flowers, to the station by a pair of his strong mares. And when their great comrade rang the last farewell song from the tower, everyone was moved to tears, because the little bell had been hanging there since 1792 in the lines of the Rateče bell tower, while the middle one dated from 1747. We hoped that at least the big bell would remain. But even that was not spared. It was taken down on 27th August 1917 and taken to who knows where. Our smallest bell, which we took from the bell tower of St. Thomas’s church and hung in the bell tower of the parish church, rang out in farewell. That is the only one we have left.’

The dispossession of the bells and their farewell was also described by Andrej Krajec, the priest of Kranjska Gora: ‘In order to save the big bell, I gave all the others from the parish church and Podkoren, all of them except the smallest one. Due to the age of the bells in the parish church, I could not save any of them, because they were all cast in 1868. The big bell and the medium-sized one were of a very venerable age, but I sacrificed everything for the big one. The pictures speak for themselves quite clearly, and the time at which this was done is even visible. The bells can also be separated by size. We accompanied the bells with Mr. Kres to the railway station. We waited for the bell from Podkoren, then we went in a procession to the station all the while praying with rosary beads. The people were so outraged that I feared a serious riot. Although I was extremely upset, the chaplain and I had to calm the people down. Before leaving for the station, the church choir sang a few songs to bid the bells farewell.’

Odvzeti zvonovi na Jesenicah (hrani: GMJ).

The removed bells in Jesenice (held by: Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

7. ŽELEZNICA V OBDOBJU MED OBEMA VOJNAMA

Konec oktobra 1918 je nastala Država Slovencev, Hrvatov in Srbov, Avstro-Ogrska pa je svojo razpustitev doživela dva dneva kasneje. Po končani vojni je prišlo do bojev za severno mejo med slovenskimi in avstrijskimi enotami, kjer so potekale bitke za etnično mešano ozemlje Koroške in Štajerske. Kmalu so sledili tudi italijanski poizkusi zasedbe delov slovenskega ozemlja, med njimi Gornjesavske doline, Jesenic, Bleda in Bohinja, saj so s tem želeli dobiti popoln nadzor na železniško progo Jesenice–Gorica. Temu se je zoperstavil Kranjskogorčan Karel Šefman (1889–1973), ki je kot avstro-ogrski vojak izkusil boje v prvi svetovni vojni, po prihodu s fronte pa je takoj začel zbirati prostovoljce za obrambo domače doline, tako pred Italijani kot tudi pred Avstrijci. Kot se je spominjal Alojz Smolej, borec v Šefmanovi četi, so Italijani že kmalu silili prek Vršiča v Kranjsko Goro in iz smeri Trbiža proti Jesenicah, a so jih borci čete uspešno zaustavili. Zanimiv dogodek, povezan z železnico, je opisal sam Karel Šefman takole: »Januarja 1919. leta so Italijani poskušali prodreti do Jesenic, in sicer kar po železniški progi. Pripravljeni so bili celi transporti do zob oboroženih vojakov. Za to je zvedel železničar Franc Smolej, ki me je pravočasno obvestil. V Kranjski gori je uničil kretnice. Bila je jasna in mrzla noč. Mesec je svetil, ko sem razporedil svoje fante na borbene položaje v Ratečah. Dve strojni puški sta držali v šahu cesto pri Jalnovi žagi, dve pa železniško progo … Po cesti je pripeljala kolona tovornjakov, po progi pa vlak. Z nekaj rafali smo opozorili »makaronarje«, da gre tokrat zares. Bili smo dovolj odločni, da so se nas nočni vsiljivci pošteno ustrašili. Ročno so opustili svojo namero, se obrnili in jo urezali nazaj proti Trbižu.«

Po ustalitvi meje v Ratečah med Kraljevino Srbov, Hrvatov in Slovencev ter Kraljevino Italijo je železnica izgubila na pomenu, šele leta 1921 pa so potniški vlaki na poti iz Italije zopet ustavljali v Planici, saj je bilo zaradi carinskih razlogov to prej prepovedano.

- THE RAILWAY IN THE INTERWAR PERIOD

At the end of October 1918, the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs was created, and Austria-Hungary was dissolved two days later. After the end of the war, there were battles for the northern border between Slovenian and Austrian units, where battles were fought for the ethnically mixed territories of Carinthia and Styria. Italian attempts to occupy parts of Slovenian territory soon followed, including the Upper Sava Valley, Jesenice, Bled and Bohinj, as they wanted to gain complete control over the Jesenice–Gorica railway line. Karel Šefman (1889-1973) from Kranjska Gora was against this; as an Austro-Hungarian soldier he experienced combat in World War I, and after returning from the front, he immediately began to gather volunteers to defend his home valley, both against the Italians and the Austrians. As Alojz Smolej, a fighter in Šefman’s volunteer company, recalled, that the Italians soon forced their way over the Vršič pass to Kranjska Gora and from the direction of Tarvisio towards Jesenice, but the troop’s volunteer fighters succeeded in stopping them. Karel Šefman himself described an interesting event related to the railway as follows:

‘In January 1919, the Italians tried to penetrate to Jesenice, namely along the railway line. Entire transports were prepared with soldiers armed to the teeth. Franc Smolej, a railway worker, found out about this and informed me in time. He destroyed the switches in Kranjska gora. It was a clear and cold night. The moon was shining when I deployed my lads to battle positions in Rateče. Two machine guns kept the road at the Jalen sawmill in check, and two monitored the railway line… A convoy of lorries came along the road, and a train along the railway line. We warned the Italians using a few blasts that this time it was for real. We were determined enough that we succeeded in terrifying the nocturnal intruders. They abandoned their intention, turned and made their way back towards Tarvisio.’

The railway lost its importance following the establishment of the border in Rateče between the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and the Kingdom of Italy, and it was not until 1921 that passenger trains on their way from Italy once again stopped in Planica, as doing so was previously prohibited for customs reasons.

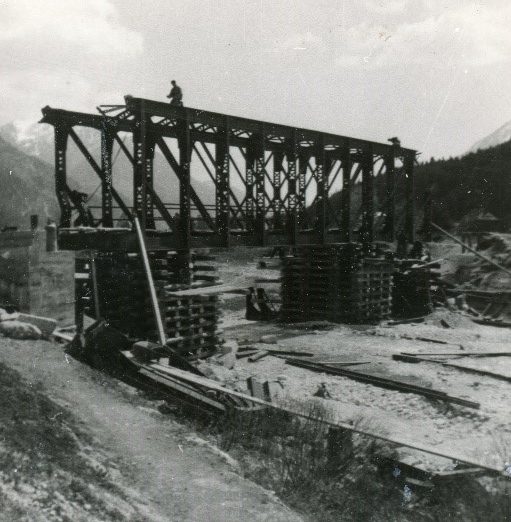

- RAZGIBANO ŽIVLJENJE MOSTU V KRANJSKI GORI

Zgodovina železniškega mostu čez Pišnico v Kranjski Gori je izjemno razgibana in zanimiva.

Most čez Pišnico je ob izgradnji meril okrog 44 metrov, postavljen pa je bil na temelje, narejene iz kamnitih blokov. Leta 1915 se je zaradi začetka bojev na soški fronti železniški promet v smeri Kranjske Gore izjemno povečal. Zaradi bojazni, da konstrukcija mostu ne bo zdržala teže tudi do sto vojaških vlakov, ki so dnevno vozili za fronto potrebni material, so most podprli s petimi lesenimi podporniki, postavljenimi na kamnite temelje. Po koncu prve svetovne vojne so te podpornike odstranili.

Do začetka druge svetovne vojne na mostu ni bilo posebnih dogodkov, kar se je dramatično spremenilo 6. aprila 1941 ob napadu sil osi na takratno Kraljevino Jugoslavijo. Tega dne je zgodaj zjutraj ob prvi zori lokalni gasilec Sajbic prebivalce hiš v bližini železniškega in cestnega mostu prišel opozorit, naj odprejo okna, ker bodo mostova razstrelili. Pri tem naj bi rekel: »Bodite pripravljeni, močno bo počilo, okna imejte odprta zaradi zračnega udara, železniški most pri Koširju bodo šprengali.« Kako uro po tem opozorilu sta bila mostova razstreljena, v istem obdobju na začetku vojne pa so minirali tudi železniški čez Savo pri Gozdu Martuljku. Kranjskogorski most je bil razstreljen na obeh koncih, vendar dokaj nespretno, zato so most popravili že v dobrem mesecu dni. Popravila mostu se je nova nemška oblast lotila na zanimiv način. Oba poškodovana konca mostu so odstranili, nepoškodovan srednji del na strani proti Kranjski Gori postavili na skorajda nepoškodovan temelj, na drugem koncu pa postavili na kamnitem temelju lesen podpornik. Razdaljo med novim lesenim podpornikom in železniškim nasipom so premostili z novo začasno konstrukcijo. Lesen vmesni podpornik je predvsem zaradi vlage postal dotrajan v pričetku petdesetih let, zato so ga nadomestili z betonskim, v začetku osemdesetih let so odstranili začasno konstrukcijo med mostom in železniškim nasipom ter nasip podaljšali do betonskega podpornika. Dela so bila izvedena sočasno z izgradnjo nove obvoznice v Kranjski Gori. Danes preko »skrajšanega« mostu poteka kolesarska steza.

- THE VARIED HISTORY OF THE BRIDGE IN KRANJSKA GORA

The history of the railway bridge over the river Pišnica in Kranjska Gora is extremely varied and interesting. The bridge over Pišnica, which was built on foundations made of stone blocks, measured around 44 metres when it was constructed. In 1915, railway traffic in the direction of Kranjska Gora increased tremendously due to the start of fighting on the Soča Front. As a result of fear that the structure of the bridge would not withstand the weight of up to a hundred military trains that on a daily basis transported materiel needed for the Front, the bridge was reinforced with five wooden supports placed on stone foundations. These supports were removed following the end of World War I.

No significant events occurred on the bridge until the beginning of World War II. However, a dramatic change came on 6th April 1941, when the Axis powers attacked the then Kingdom of Yugoslavia. That day, early in the morning at the first light of dawn, the local firefighter Mr. Sajbic came to warn the residents of the houses near the railway and road bridges to open their windows because the bridges were about to be blown up. He is said to have warned: “Be ready, there will be a big explosion, keep your windows open because of an air strike, the railway bridge near the Košir house will be blown up.” An hour after this warning, two bridges were blown up, and in the same period at the beginning of the war, the railway bridge across the Sava River near Gozd Martuljek was also mined.

The Kranjska Gora bridge was blown up at both ends, albeit quite ineptly, so the bridge was repaired in just over a month. The new German authorities adopted an interesting approach to tackling the repair of the bridge. Both damaged ends of the bridge were removed, the undamaged middle part on the side facing Kranjska Gora was placed on an almost undamaged foundation and a wooden support was placed on the stone foundation at the other end. The space between the new wooden support and the railway embankment was bridged with a new temporary structure. The wooden intermediate support became worn out mainly due to damp in the early 1950s, so it was replaced with a concrete one. In the early 1980s, the temporary structure between the bridge and the railway embankment was removed and the embankment was extended to the concrete support. The works were carried out simultaneously with the construction of a new bypass in Kranjska Gora. Today, a bicycle path runs over the ‘shortened’ bridge.

Nemški vlak na železniški postaji v Gozdu Martuljku (hrani: GMJ).

A German train at the train station in Gozd Martuljek (held by: Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

9. PODOBE MOSTU V KRANJSKI GORI

9. IMAGES OF THE BRIDGE IN KRANJSKA GORA

Dvignjen osrednji del mostu na začasnih lesenih podpornikih (hrani: GMJ).

The central part of the bridge hoisted onto temporary wooden supports (held by: Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

Pogled na poškodovani del konstrukcije mostu (hrani: GMJ).

A view of the damaged part of the construction of the bridge (held by: Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

Popravilo mostu (hrani: GMJ).

Repair of the bridge (held by: Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

Preizkus novega mostu (hrani: GMJ).

Testing of the new bridge (held by: Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

10. BUNKERJI

Tako kot v prvi svetovni vojni je imela tudi v drugi svetovni vojni železnica velik pomen za vojsko. Nemške okupacijske sile so po železnici transportirale svoje enote in material, potreben za vojskovanje. Kot je zapisano na partizanskem propagandnem letaku, je bil prevoz »Ahilova peta vsega nemškega vojnega sistema. Prav zaradi tega pomen Slovenije daleč prekaša njen obseg«. Partizansko gibanje je tako močno pozivalo k sabotažnim akcijam železniških prog in mostov ter tovrstne akcije tudi izvajalo na številnih krajih širom Slovenije. Kot so zapisali, je bila »vsaka pretrgana železnica« tudi »pretrgana nemška žila – dovodnica«. Posledično je bilo varovanje železniške infrastrukture za nemško vojsko izjemno pomembno, na trasi železnice v Gornjesavski dolini pa so med vojno zgradili tudi nekaj bunkerjev, s katerimi so želeli varovati tako železniške mostove kot tudi bližnjo cestno povezavo. O samih bunkerjih ni znanih veliko podatkov. Zgrajeni so bili ob železniškem mostu na Belci, ob mostu pri Podklužah, pri Pogorišču, Gozdu Martuljku in v Kranjski Gori. Danes si lahko še vedno ogledamo prve štiri, tistega v Kranjski Gori pa so ob gradnji nove ceste skozi naselje podrli.

Kdaj točno so zgradili omenjene bunkerje, zaenkrat ni znano. Po pričevanjih nekaterih prebivalcev Gornjesavske doline, ki so drugo svetovno vojno doživeli kot otroci, so bili bunkerji zgrajeni v drugi polovici vojne, morda celo bolj proti njenemu koncu. Zanimivost bunkerjev je njihov nenavaden izgled, ki ne spominja na značilno nemško utrdbeno arhitekturo. Edini značilnejši nemški element so stopničasto zgrajene pravokotne strelne line, drugače pa bunkerji bolj spominjalo na italijanske ali celo jugoslovanske objekte. Ker nobeden med ohranjenimi primerki nima strehe, se predvideva, da nikoli niso bili zares dokončani, vendar pa so bili, glede na ustna pričevanja očividcev, bunkerji zagotovo v uporabi, saj so jih stražarji uporabljali za varovanje mostov v primeru morebitne partizanske sabotaže.

- BUNKERS

As was the case in World War I, the railway was of great importance to the army in World War II. The German occupying forces transported their troops and materiel necessary for warfare by rail. As written on a partisan propaganda leaflet, transportation was the ‘Achilles heel of the entire German war system. It is for this reason that Slovenia’s importance far exceeds its scope.’ The partisan movement strongly called for sabotage of railway lines and bridges and carried out such actions in many places around Slovenia. As they wrote, ‘every broken railway’ was also ‘a broken German artery – vein’. As a result, protecting the railway infrastructure was extremely important for the German army, and during the war they also built some bunkers on the railway route in the Upper Sava Valley, with the intention of protecting both the railway bridges and the nearby road connection. Not much information is known about the bunkers themselves. They were built next to the railway bridge in Belca, next to the bridge near Podkluže, at Pogorišče, Gozd Martuljek and in Kranjska Gora. The aforementioned four can still be seen today, but the one in Kranjska Gora was demolished during the construction of a new road through the village.

It is not yet known when exactly the aforementioned bunkers were built. According to the testimonies of some residents of the Upper Sava Valley who experienced World War II as children, the bunkers were built in the second half of the war, perhaps even more towards its end. The unusual appearance of the bunkers is interesting, as they do not resemble typical German fortress architecture. The only characteristically German element is the staggered rectangular embrasures, but otherwise the bunkers are more reminiscent of Italian or even Yugoslav facilities. Since none of the preserved examples have a roof, it is assumed that they were never really completed, but according to the oral testimonies of eyewitnesses, the bunkers were definitely in use as the guards used them to protect the bridges in the event of possible partisan sabotage.

Bunker pri Pogorišču (foto: U. Košir, 2024).

A bunker at Pogorišče (photo: U. Košir, 2024).

Bunker v Gozdu Martuljku (foto: U. Košir, 2023).

A bunker in Gozd Martuljek (photo: U. Košir, 2023).

11. LETALSKI NAPADI NA PROGI JESENICE–RATEČE MED DRUGO SVETOVNO VOJNO

Leto 1944 je bilo prelomno v poteku druge svetovne vojne. Poleti so se zavezniške armade izkrcale v Normandiji, skoraj istočasno je bil osvobojen Rim, s čimer se je fronta v Italiji pomikala vedno bolj proti severu. Napredovanje zaveznikov v Italiji je omogočilo gradnjo letališč vse bližje Sloveniji, ki so omogočala polete bombniških in lovskih letal tudi nad Gornjesavsko dolino. Prvi poleti teh letal so zabeleženi v pozni jeseni leta 1944, nadaljevali pa so se do konca vojne.

Na območju Gornjesavske doline se je prvi zabeleženi napad na vlak zgodil 3. februarja 1945 okoli enajste ure dopoldne. Iz smeri Trbiža sta prileteli letali P-38 Lightning iz 2. zračne sile, 1. lovske skupine, 94. lovske eskadrilje in napadli vlak, ki je stal tik ob italijanski meji pri Ratečah. Na srečo pri napadu ni bilo žrtev, po poročilu pilotov pa sta popolnoma uničili vsaj tri vagone, zadeli sta tudi lokomotivo. Na cvetno nedeljo 25. marca 1945 sta dve letali Spitfire 4. eskadrilje Južnoafriškega letalstva mitraljirali lokomotivo, ki je stala blizu skakalnice v Ratečah. Strojevodja, kurjač in železničar so pravočasno zagledali letali in pobegnili v gozd, lokomotiva pa je bila pri napadu uničena. Napad na vlak se je zgodil tudi v današnjem naselju Gozd Martuljek. Glede na razpoložljive dokumente izvemo, da sta 20. februarja 1945 okoli enajste ure dopoldne letali Spitfire 2. eskadrilje Južnoafriškega letalstva mitraljirali vlak med železniškim mostom in postajališčem Gozd. Po pričevanju Alojza Mertlja, ki je takrat kot 12-letni deček živel v Srednjem vrhu, sta ga zelo nizko preleteli dve letali, se strmoglavo drugo za drugim spustili v dolino, mitraljirali vlak, strmo dvignili in odleteli. Iz lokomotive se je nato močno pokadilo, dvignil se je velik oblak pare.

Tarča letalskega napada so bile tudi Jesenice, ko je 23 letal Consolidated B-24 J Liberator ameriške 15. zračne sile Ameriškega armadnega letalstva 1. marca 1945 na Jesenice odvrglo 94 letalskih 225-kilogramskih rušilnih bomb, polnjenih z razstrelivom RDX. Kot cilj napada ameriški arhivi navajajo območje železniške postaje. Žal so bombardirji merili slabo, poškodovana je železniška postaja sicer bila, dve bombi sta prileteli med železniške tire, pri čemer je bilo uničenih nekaj vagonov in tirov. Škoda na cilju je bila tako relativno majhna, razdejanje mesta Jesenice pa žal precejšnje. Napad je povzročil številne smrtne žrtve tako med prebivalci kot tudi med pripadniki nemških oboroženih sil.

- AIR RAIDS ON THE JESENICE–RATEČE LINE DURING WORLD WAR II

The year 1944 was a turning point in the course of World War II. In the summer, the Allied armies landed in Normandy and almost at the same time Rome was liberated, which enabled the front in Italy to move further and further north. The advance of the Allies in Italy facilitated the building of airports ever closer to Slovenia, which allowed bomber and fighter planes to fly over the Upper Sava Valley. The first flights by these aircraft were recorded in the late autumn of 1944 and continued until the end of the war.

The first recorded attack on a train in the Upper Sava Valley took place on 3rd February 1945, at around eleven o’clock in the morning. Two P-38 Lightning aircraft from the 2nd Air Force, 1st Fighter Group, 94th Fighter Squadron flew in from the direction of Tarvisio and attacked the train, which was standing right next to the Italian border near Rateče. Fortunately, there were no casualties in the attack and, according to the pilots’ report, at least three wagons were completely destroyed and a locomotive was also hit. On Palm Sunday, 25th March 1945, two Spitfire planes of the 4th Squadron of the South African Air Force machine-gunned a locomotive that was standing near the ski jump in Rateče. The driver, stoker and railwayman saw the planes in time and fled into the forest, however, the locomotive was destroyed in the attack.

An attack on a train also took place in the area that is today the village of Gozd Martuljek. According to available documents, at around eleven o’clock in the morning on 20th February 1945 two Spitfire planes of the 2nd squadron of the South African Air Force machine-gunned a train between the railway bridge and the Gozd station. According to a testimony by Alojz Mertelj, who at the time, aged 12, lived in Srednji vrh, two planes flew over him very low, descended sharply one after the other into the valley, machine-gunned the train, took off sharply and flew away. The locomotive then began to smoke heavily and a large cloud of steam rose.

Jesenice was also the target of an air attack, when 23 Consolidated B-24 J Liberator aircraft of the US 15th Air Force of the US Army Air Force dropped ninety-four 225-kilogramme demolition bombs filled with RDX explosives on Jesenice on 1st March 1945. US archives list the area of the train station as the target of the attack. Unfortunately, the bombers aim was poor, albeit the railway station was damaged and two bombs landed between the railway tracks, destroying several wagons and tracks. The damage sustained at the target was thus relatively minor, however, the destruction of the town of Jesenice itself was unfortunately considerable. The attack resulted in many deaths among the population as well as members of the German armed forces.

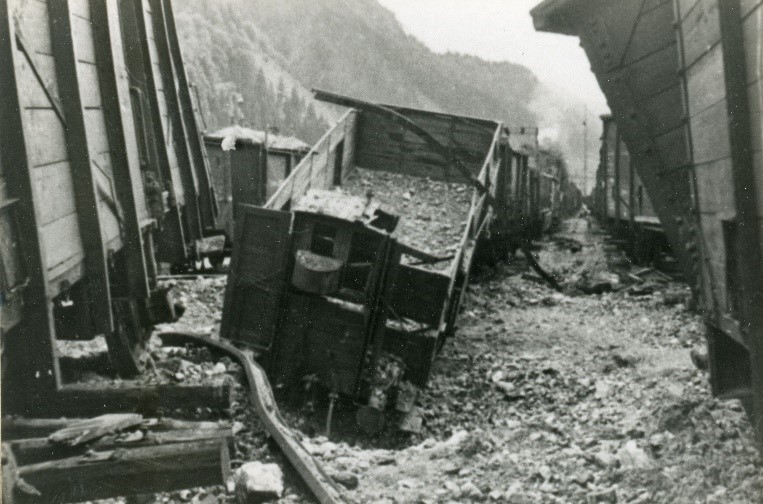

Posledice bombardiranja na jeseniški železniški postaji (hrani: GMJ).

The consequences of the bombing on the Jesenice railway station (held by: Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

12. ŽELEZNICA PO DRUGI SVETOVNI VOJNI

Železnica je predstavljala pomembno transportno sredstvo za ljudi, ki so delali v jeseniški železarni ali pa so imeli službo izven območja Gornjesavske doline. Z vlaki so v šolo hodili tudi šolarji, množično pa so jih uporabljali izletniki in športni navijači, predvsem v času smučarskih skokov v Planici. Po podatkih časopisa Glas se je sicer leta 1965 na delo in v šolo z vlakom vozilo okoli 1000 ljudi iz celotne Gornjesavske doline. Že ob tekmi smučarskih skakalcev v Planici leta 1948, ko je prva dneva tekmovalo le 19 skakalcev, je bilo poleg rednih vlakov organiziranih še osem dodatnih vlakov. Trije iz Ljubljane, po eden iz Zagreba, Kranja, Jesenic, Reke in Celja, tekmo pa si je ogledalo več kot 10.000 gledalcev. Dne 12. marca 1952 je bila v Planici otvoritev nove Bloudkove skakalnice, slavje pa je bilo združeno tudi z mednarodnim tekmovanjem. Samo podjetje Putnik je organiziralo 45 izrednih vlakov v Planico. Navijači pa niso obiskovali le tekem smučarskih skokov, temveč tudi smučarske tekme v Kranjski Gori. Leta 1964 so zaradi spremenjenega časa izvedbe tekme obiskovalci s posebnim vlakom tekmo v celoti zamudili, kar je šef turističnega transportnega biroja opisal tako: »/…/dne 29. 2. 1964 je organiziral turistično transportni biro JŽ [Jugoslovanskih železnic] Ljubljana poseben vlak iz Ljubljane v Kranjsko goro, da bi omogočil širši javnosti, predvsem dijakom, ogled mednarodne smučarske prireditve. Prireditveni odbor nam je javil, da bo začetek tekmovanja ob 11:00 uri. Na osnovi teh podatkov je bil izdelan vozni red posebnega vlaka, ki je imel določen odhod iz Ljubljane ob 7:50 in prihod v Kranjsko goro ob 10:00 uri. /…/Predvsem je bilo iznenadeno vodstvo vlaka, ko prav do samega prihoda v Kranjsko goro ni bilo obveščeno o preložitvi tekmovanja za eno uro prej.«

Težave na progi Jesenice–Rateče je v zimskem času pogosto povzročal sneg, ki ga je bilo precej več, kot smo ga deležni v današnjih časih. Nekdanji šef železnike postaje Jesenice France Jerala se je spominjal, da je sneg v »dolini« predstavljal veliko težavo, ki so jo s staro mehanizacijo stežka odpravili. Leta 1952 je februarja v štirih dnevih zapadlo skoraj dva metra snega, v Ratečah pa skoraj dva metra in pol. Nastopil je popoln kolaps železničarskega prometa, vsi zaposleni pa so morali poprijeti za lopate in odmetavati sneg s proge, kar je trajalo kar pet dni.

- THE RAILWAY AFTER WORLD WAR II

The railway was an important means of transport for people who worked in the Jesenice ironworks or those who worked outside the area of the Upper Sava Valley. Children also went to school by train and it was used en masse by day trippers and sports fans, mainly during the ski jumping competition in Planica. According to information from the Glas newspaper, around 1,000 people from the entire Upper Sava Valley went to school or work by train in 1965. By the time of the ski jumping competition in Planica in 1948, when only 19 competitors took part on the first day, in addition to scheduled trains there were an additional eight trains; three from Ljubljana, and one each from Zagreb, Kranj, Jesenice, Rijeka and Celja. The competition was watched by 10,000 spectators. The opening of the new Bloudek ski jump took place on 12th March 1952 and an international competition also took place as part of the festivities. The company Putnik alone organised forty-five additional trains to Planica. The fans not only visited the ski jumping competitions but also ski competitions in Kranjska Gora. In 1964, due to a change in the schedule for the competition, visitors arriving on a special train missed the competition in its entirety, which the manager of the tourist transport bureau described thus: ‘/…/ On 29.2.1964 the Ljubljana Yugoslav Railways transport bureau organised tourist transport by a special train from Ljubljana to Kranjska gora in order that the wider public, particularly students, could watch the international ski event. The event committee informed us that the start of the competition would be at 11am. A timetable was put together on the basis of that information. The train was scheduled to leave Ljubljana at 7.50am and arrive in Kranjska gora at 10am. /…/ The train management was therefore very surprised that they were not informed that the start time of the competition had been moved forward by an hour, i.e. prior to the arrival of the train in Kranjska gora.’

Snow often caused problems on the Jesenice-Rateče railway line in winter; there was significantly more snow then than these days. The former manager of the Jesenice railway station, France Jerala, recalls how the snow in the ‘valley’ caused great problems, which, due to the old machinery, was difficult to remove. Over four days in February 1952 almost two metres of snow fell, and in Rateče almost two-and-a-half metres. It resulted in a total collapse of railway traffic, all employees had to muck in and shovel snow from the track, which took five days.

Pogled na skakalnici v Planici, kamor so obiskovalci množično hodili z vlakom (hrani: GMJ).

A view of the ski jump in Planica, which visitors travelled en masse by train (held by: Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

13. ŽELEZNIŠKA NESREČA NA BELCI

Edina zabeležena večja železniška nesreča na progi Jesenice–Rateče se je zgodila v zgodnjih jutranjih urah 12. novembra 1951. Nesreča je žal terjala tudi smrtno žrtev, povzročilo jo je izredno močno neurje z dežjem. V časopisu Slovenski poročevalec z dne 13. 11. 1951 je bil objavljen obsežen članek o nesreči, ki ga deloma povzemamo. V noči iz nedelje na ponedeljek je na širšem območju Mojstrane divjalo neurje, saj se je v okolici Kepe v Karavankah utrgal oblak. Posledično je v nočnih urah potok Belca močno narastel, zalilo je kleti nekaterim hišam, veter pa je odnesel tudi nekaj streh. V časopisu lahko preberemo, da je voda odnesla celo celoten hlev z živalmi vred. Zaradi nevarnosti so progovni čuvaji opozorili osebje na železniški postaji o možni nevarnosti na progi med Mojstrano in Belco. Strojevodjo so zato opozorili, da naj prilagodi hitrost vlaka na samo 12 km/h. Kljub temu se je pod jutranjim vlakom ob 5.15 udrl del železniške proge tik za mostom pri naselju Belca. Za lokomotivo je bil pripet službeni vagon, v katerem se je peljal vlakovodja Anton Klinar, ki je pri tem izgubil življenje. Iztiril je tudi prvi potniški vagon, ki se je prevrnil, v njem pa so bili trije potniki lažje poškodovani. Ostali potniški vagoni so na srečo ostali na tirih. Na železniški postaji na Jesenicah so takoj po prejetju obvestila o nesreči na kraj nesreče poslali poseben vlak z delavci, ki so pomagali poškodovancem in odstranjevali posledice nesreče. Sreča v nesreči je bila, da je bil strojevodja vlaka pravočasno opozorjen na možno nevarnost, zato je vlak vozil z zelo majhno hitrostjo. V primeru, da bi vlak peljal z normalno hitrostjo, bi bile posledice katastrofalne. Ob neurju je bil močno poškodovan tudi cestni most čez hudourniški potok Belca, zaradi česar je bil promet iz Jesenic proti Kranjski Gori popolnoma prekinjen.

- RAILWAY ACCIDENT AT BELCA

The only documented major railway accident on the Jesenice–Rateče line occurred in the early hours of 12th November 1951. The accident, which was caused by a massive rainstorm unfortunately also claimed a fatality. A lengthy article about the accident was published in the Slovenski poročevalec newspaper on 13th November 1951, which has been partially summarised below.

On Sunday night a cloudburst occurred, which led to a storm that raged in the wider area of Mojstrana. As a result, the Belca stream rose dramatically during the night, flooded the cellars of some houses and a number of roofs were blown off by the wind. The newspaper article states that the water even washed away an entire barn with animals. The track inspector warned the staff at the railway station about the possible danger on the line between Mojstrana and Belca.

The train driver was therefore warned to reduce the speed of the train to just 12 km/h. Nevertheless, at 5.15 a.m., part of the railway line just after the bridge near the settlement of Belca caved in under the morning train. At the time, the train’s conductor, Anton Klinar, was in the service wagon, which was attached to the locomotive, and as a result of the service wagon derailing he lost his life. It also derailed the first passenger car, which overturned and three passengers were slightly injured. Fortunately, the other passenger wagons remained on the tracks. Immediately after receipt of a notification about the accident, a special train with workers was sent from the railway station in Jesenice to the scene of the accident to help the injured and remove the debris. It was fortunate that the train driver had been alerted to the possible danger in time, therefore the train was travelling at a very low speed. If it had been travelling at normal speed, the consequences would have been catastrophic. The road bridge over the torrential Belca steam was also badly damaged during the storm, as a result of which traffic from Jesenice to Kranjska Gora was halted entirely.

- UKINITEV PROGE

Kar stori neumnež,

tristo pametnih ne popravi!

(ljudski pregovor)

Jeseniški časopis Železar je 19. februarja 1966 objavil novico o dokončni in nepreklicni ukinitvi prometa na Gornjesavski železnici. Novica je napovedala konec 96-letne zgodovine železnice, ki je krajem od Jesenic do Rateč pomenila vez s svetom in je omogočila vsestranski razvoj Gornjesavske doline: železarstvo na Jesenicah, cementarna v Mojstrani, začetki gorniškega in nekaj časa kasneje zimskega turizma ter s tem povezanimi prvimi hoteli v Gornjesavski dolini, prevozi krajanov na delo in dijakov v šole. Znane so zgodbe o pravih romanjih z vlaki v Planico, kamor je zaradi izrednega zanimanja za smučarske skoke in polete peljalo tudi do 15 posebnih podaljšanih vlakov dnevno.

Prvi namigi o ukinitvi krajših železnic v takratni Jugoslaviji so se pojavili v javnosti sredi leta 1964. Po zatrjevanju politikov v Beogradu naj bi šlo predvsem za racionalizacijo, saj naj takšne krajše železnice ne bi bile ekonomsko rentabilne. Verjetno res, vendar v primeru Gornjesavske železnice to ne drži. V tem času se je po progi redno dnevno vozilo okoli 600 delavcev na delo na Jesenice, okoli 200 dijakov pa v šole. Prišteti je potrebno še gornike, smučarje in vse ostale obiskovalce Gornjesavske doline. Vlaki so bili zanesljivo polni, odločilno pa je bilo dejstvo, da bi bila potrebna velika vlaganja v posodobitev Gornjesavske železnice. Uprava Združenega železniškega transportnega podjetja Ljubljana je tako slepo sledila politični odločitvi iz Beograda in ukinila celo vrsto krajših železnic po Sloveniji. Krajani Gornjesavske doline so ukinitvi ostro nasprotovali, sklicali so celo vrsto sestankov med predstavniki Železniškega transportnega podjetja Ljubljana, Občine Jesenice in Krajevne skupnosti Kranjska Gora. Predstavniki Krajevne skupnosti Kranjska Gora so odpotovali celo v Beograd, kjer so dokazovali upravičenost ohranitve Gornjesavske železnice. Naleteli so na gluha ušesa, le datum ukinitve je bil zaradi skokov v Planici prestavljen iz 1. januarja na 31. marec 1966.

- CLOSURE OF THE RAILWAY

A fool’s work cannot be undone by three hundred wise men.

(folk proverb)

On 19th February 1966 the Jesenice newspaper Železar published news of the final and irrevocable closure of the Upper Sava railway. The news signalled the end of the 96-year history of the railway, which meant a tie to the world for the villages and settlements from Jesenice to Rateče and enabled all-round development of the Upper Sava Valley: ironworking in Jesenice, the cement works in Mojstrana, the beginnings of mountaineering tourism and some time later winter tourism, and in that regard the first hotels in the Upper Sava Valley, the transport of inhabitants to work and students to school. There are stories of actual pilgrimages by train to Planica, where, due to exceptional interest in ski jumping and ski flying, up to fifteen special extended trains ran each day.

The first hints about closure of the shortest railway in the then Yugoslavia appeared in public in the middle of the year 1964. According to assurances by politicians in Belgrade it was primarily a matter of rationalisation, since such a short railway was not economically viable. That may be the case, however, in the case of the Upper Sava railway it is not true. During that time around 600 workers commuted to work to Jesenice on a daily basis and around 200 students to school. On top of that it is necessary to count mountaineers, skiers and all the other visitors to the Upper Sava Valley. The trains were always full, however, the decisive fact was that a lot of investment would be required in modernisation of the Upper Sava railway. The board of the United Railway Transport Company Ljubljana blindly followed the political decision from Belgrade and closed a whole series of short railways in Slovenia. The inhabitants of the Upper Sava Valley strongly opposed the closure and convened a whole series of meetings between representatives of the Ljubljana Railway Transport Company, the Municipality of Jesenice and the Local Community of Kranjska Gora. Representatives of the Local Community of Kranjska Gora even travelled to Belgrade, where they demonstrated the justification of preserving the Upper Sava. Their protests fell on deaf ears and only the date of the closure was moved from 1st January 1966 to 31st March 1966 due to the ski jumps in Planica.

Potniki vstopajo na vlak v Kranjski Gori (hrani: GMJ).

Passengers boarding the train in Kranjska Gora (held by: Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

15. ZADNJE VOŽNJE VLAKOV

Zadnji vlaki na progi Jesenice–Planica so peljali 31. marca. Tega dne se je ob 6. uri in 21 minut zjutraj z Jesenic proti postaji Planica odpravil vlak z lokomotivo št. 17-072, katerega strojevodja je bil Vinko Šumi, kurjač pa Anton Kolac. Vlak je po voznem času v Planico prispel ob 7. uri in 10 min in se nato vrnil proti Jesenicam ob 12. uri in 48 minut, kamor je prispel ob 13. uri in 32 minut. Vmes je potovanje opravila tudi vlakovna kompozicija z lokomotivo št. 17-069 (Leon Mlakar in Jože Humar), zadnji vlak s potniki pa se je z Jesenic odpravil ob 22. uri in 22 minut, v Planico pa je prispel ob 23. uri in 11. minut. Z lokomotivo št. 17-072 sta opravljala Jože Egart in kurjač Jure Tokič. Kot se spominja Vinko Šumi, se je z zadnjim vlakom »/…/ pripeljala velika množica ljudi z zastavami, raznimi transparenti. /…/ Navzoči so bili pevci in godba na pihala. Bilo je kot na pogrebu, zadnje slovo od vlaka. Prazen vlak je iz Doline odpeljal 1. aprila. Strmeli smo vanj, slišali ropot in piskanje lokomotive, čez čas pa je z njim vse utihnilo za vedno«. Časopis Glas je 1. aprila o ukinitvi proge zapisal: »Čeprav bi pred leti prebivalci Gornjesavske doline sprejeli novico o ukinitvi železniške proge na relaciji Jesenice–Rateče kot neslano prvoaprilsko šalo, je danes, točno prvega aprila, postala resnica. Vlak ne vozi več. Utihnil je glas lokomotiv in ostal bo le spomin.«

Že tri mesece po ukinitvi je bila proga med Ratečami in Hrušico tudi podrta, del tirov in ostale infrastrukture, z izjemo železniških mostov, pa se je ohranil le pri Hrušici. Zaradi potrebe po povečanju javnega cestnega prometa na relaciji Rateče–Jesenice je poslovna enota Jesenice podjetja Ljubljana transport kupila pet novih avtobusov znamke FAP, tipa Ohrid A-11, ki so imeli 41 sedežev in 20 stojišč. Skupaj s starim voznim parkom je bilo predvidenih devet avtobusov za prevoz prebivalcev Gornjesavske doline. Po podatkih iz leta 1966 se je avtobusni promet povečal za kar 36 voženj dnevno.

- THE LAST TRAINS MAKE THEIR FINAL JOURNEY

The last trains on the Jesenice–Planica line left on 31st March 1966. On that day, at 6.21 a.m., a train with locomotive no. 17-072, the driver of which was Vinko Šumi and the stoker was Anton Kolac, left Jesenice towards the station in Planica. According to the timetable, the train arrived in Planica at 7.10 a.m. then set off to return to Jesenice at 12.48 p.m., where it arrived at 1.32 p.m. In the meantime, a train composition with locomotive no. 17-069 (Leon Mlakar and Jože Humar), and the last passenger train left Jesenice at 10.22 p.m. and arrived in Planica at 11.11 p.m. with locomotive no. 17-072 operated by Jože Egart and stoker Jure Tokič.

As Vinko Šumi remembers, ‘/…/ a large crowd of people with flags and various banners were on the final train. /…/ There were singers and a brass band. It was like a funeral, the train’s last farewell. An empty train left the valley on 1st April. We stared at it, heard the rumble and whistle of the locomotive, and after a while everything connected to the train went silent forever.’ On 1st April, the newspaper Glas wrote the following about the closure of the railway line: ‘Although years ago the inhabitants of the Upper Sava Valley would have accepted the news of the closure of the railway line on the Jesenice–Rateče route as an unsavoury April Fool’s joke, today, on 1st April itself, it became the truth. The trains are no longer running. The sound of locomotives has fallen silent and will remain only a memory.’

Just three months after its closure, the line between Rateče and Hrušica was demolished with the exception of some of the railway bridges. Only part of the tracks and the rest of the infrastructure was preserved near Hrušica. Due to the need to increase public transport on the Rateče-Jesenice route, the Jesenice branch of the Ljubljana transport company bought five new FAP A11 Ohrid buses, which had forty-one seats and space for twenty standing passengers. Together with the old fleet, it was planned that nine buses would transport the inhabitants of the Upper Sava Valley. According to data from 1966, bus traffic increased by as many as thirty-six trips per day.

Sprevodnik Franc Grbec pri pregledu vozovnic, 31. 3. 1966 (foto: F. Makovec; hrani GMJ).

Railway conductor Franc Grbec checking tickets, 31.3.1966 (photo: F. Makovec; held by Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

Potniki se s črnimi zastavami, 31. 3. 1966 ob 24. uri na postaji Rateče–Planica poslavljajo od zadnjega vlaka (foto: F. Makovec; hrani GMJ).

Passengers with black flags, 31.3.1966 at midnight at the Rateče–Planica station bidding farewell to the last train (photo: F. Makovec; held by Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

Vlak med vožnjo proti Mojstrani, 31. 3. 1966 (foto: F. Makovec; hrani GMJ).

A train on its way towards Mojstrana, 31.3.1966 (photo: F. Makovec; held by Upper Sava Museum Jesenice).

16. ŽELEZNICA DANES

Trasa nekdanje železniške proge je dolgo časa samevala, ohranjene mostove pa je že načenjal zob časa. Objekti železniških postaj in čuvajnic so bili spremenjeni v bivalne stavbe, ki še danes spominjajo na nekdanjo »železno cesto«, ki je od leta 1870 do 1966 povezovala kraje Gornjesavske doline. Nekdanje čuvajnice, kot so npr. tiste v Podkorenu, pri Martuljku in Belci, so bile spremenjene v bivalne objekte ali v turistične apartmaje. Na enak način so bila spremenjena tudi poslopja železniških postaj, na katerih se ponekod še vidijo sledovi nekdanjih napisov z imeni krajev.

V začetku tega stoletja je bilo trasi nekdanje železnice vlito novo življenje v obliki prostora za rekreacijo – kolesarske steze. Leta 2001 je bil za kolesarski promet odprt 15-kilometrski odsek od mejnega prehoda Rateče do Gozda Martuljka, povezava z Jesenicami, ki od Mojstrane proti Martuljku večinoma poteka po trasi nekdanje železnice, pa je bila dokončno urejena nekoliko kasneje. Slikovita kolesarska pot se na odseku med Mojstrano in Ratečami od leta 2011 imenuje »Kolesarska pot Jureta Robiča« z uradno oznako D-2. Od Jesenic do mejnega prehoda v Ratečah meri približno 28 km, na svoji poti pa kolesarji premagajo 255 višinskih metrov. Na trasi nekdanje železnice lahko še vedno občudujemo železne mostove na Belci, ob poti proti Martuljku in v Kranjski Gori, vsi mostovi pa so bili do danes vsaj delno tudi obnovljeni.

Trasa kolesarske steze se od prvotne železniške trase med Mojstrano in Ratečami odcepi predvsem na predelu med Podklužami in mostom čez Savo, zahodno od Malnika ter skozi Kranjsko Goro. Drugod se je s kolesom mogoče peljati po nekdanji železnici in občudovati mostove, budnemu očesu pa ne uidejo niti nekdanje postaje in čuvajnice.

- THE RAILWAY TODAY

The route of the former railway line remained abandoned for a long time, and the preserved bridges were already showing signs of wear and tear. The railway station and guardhouse buildings were converted into residential buildings, which to this today serve as a reminder of the former ‘iron road’ that connected the places of the Upper Sava Valley from 1870 to 1966. The former guardhouses, such as those in Podkoren, Gozd Martuljek and Belca, were converted into residential buildings or tourist apartments. The railway station buildings were also converted in the same way, and traces of the former inscriptions with the names of the places can still be seen.

At the beginning of this century, the route of the former railway was given new life in the form of a recreation area – a bicycle path. In 2001, a 15-kilometre section from the border crossing at Rateče to Gozd Martuljek was opened for bicycle traffic, and the connection with Jesenice, which mostly runs from Mojstrana to Gozd Martuljek along the route of the former railway, was finally completed in later years. Since 2011, the scenic cycling route on the section between Mojstrana and Rateče has been called The Jure Robič Cycling Route and has the official designation D-2. The section from Jesenice to the border crossing in Rateče is about 28 km-long, with a total height difference of 255 metres. Along the route of the former railway, the iron bridges can still be admired in Belca and on the way to Gozd Martuljek and in Kranjska Gora; all the bridges have been at least partially restored to date.

The route of the bike track mainly branches off from the original railway route between Mojstrana and Rateče in the area between Podkluže and the bridge over the Sava river, west of Malnik and through Kranjska Gora. Elsewhere, you can ride a bike along the former railway and admire the bridges, and even the former stations and guardhouses draw one’s attention.

Kolesarska steza na trasi nekdanje proge (foto: U. Košir, 2024).

The cycle track along the former railway line (photo: U. Košir, 2024).

Trasa železnice danes predstavlja prostor za rekreacijo (foto: U. Košir, 2024).

Today, the route of the former railway is a place for recreation (photo: U. Košir, 2024).

Viri in literatura za razstavo Zgodovina ob tirih – Zgodbe z železnice Jesenice–Trbiž / Sources and literature for the exhibition History Along the Tracks – Stories from the Jesenice–Tarvisio Railway

Literatura / Literature

Andrejčič Mušič, P., 2009. Kolesarski projekti, ki jih financira Evropska unija. Ljubljana: Ministrstvo za promet, Direkcija Republike Slovenije za ceste.

Bogić, M., 1998. Pregled razvoja železniškega omrežja v Sloveniji in okolici, Die Entwicklung des Eisenbahnnetzes in Slowenien. Ljubljana : Slovenske železnice, Železniški muzej.

Brate, T., 2013. Zgodovina slovenskih železnic na razglednicah. Die Geschichte der slowenischen Eisenbahnen auf Ansichtskarten. Celje: Celjska Mohorjeva družba in Celovec: Mohorjeva založba Celovec.

Černe, V., 2003. Pol stoletja dolga pot : Borovška vas – Kranjska Gora po drugi svetovni vojni: fotomonografija. Kranjska Gora : samozaložba V. Černe.

Jenko, J., 1936–1968. Zbor člankov iz zgodovine slovenskih železnic.

Lavtižar, J., 1998. Rateška kronika Josipa Lavtižarja. Kranjska Gora: Župnijski urad.

Mohorič, I., 1968. Zgodovina železnic na Slovenskem. Ljubljana: Slovenska matica.

Rauter, D. in Rainer, H., 1992. Ein Verkehrsweg erschliesst die Alpen. St. Peter ob Judenburg: Verlag Mlakar.

Šega, J. (ur.), 2015. V zaledju soške fronte. Koper: Pokrajinski arhiv; Nova Gorica: Pokrajinski arhiv; Ljubljana: Zgodovinski arhiv; Jesenice: Gornjesavski muzej; Tolmin: Tolminski muzej.

Ude, L., 1979. Jeseniški trikot. V: Melik, V. ur. Zgodovinski časopis, l. 33, št. 3, str. 435-441.

Arhivski viri / Archival sources

Arhiv Republike Slovenije:

- SI AS 1093, Zbirka železniških načrtov, šk. 4, p.e. II/16/24020, Načrt železniške postaje Kranjska Gora.

Zgodovinski arhiv Ljubljana:

- SI_ZAL_KRA_/0133, t.e. 13, a.e. 65, Načrt dela čez Pišnico.

- SI_ZAL_KRA_/0133, t.e. 13, a.e. 65, Nemški načrt mostu v Kranjski Gori.